Deborah Klens-Bigman ◆ July 20, 2015

I introduce every new student to the swordsmanship class to the basics of our practice. We first work on the kamae (positions) for holding the sword, and the basic cuts, which make up our opening exercise, happogiri (literally, “eight-directions-cut”). This is the only part of the class that is pure technique and not kata (as I have mentioned before, all of the kata consist of “stories” of attack and defense). Happogiri is straightforward, but I think it’s not that interesting, so I also have new students try the first kata, Shohatto from the shoden (beginning) Omori ryu set. Depending on who else is in the class that night, I may also have them try a basic kumidachi (paired) kata. Taken altogether, these activities give new people a good overview of what our practice is about. Given all of the misconceptions about martial arts in general, and swordsmanship in particular, I feel that it’s important that people understand what we do from the beginning.

In Shohatto, the iaidoka begins by sitting in the kneeling position of seiza. She then responds to an attack from the front. She draws and cuts the opponent across the face, then moves forward and performs a large, downward cut. From there, she shakes the “blood” from the sword, and resheathes it. The next three kata in the Omori set are all variations on the first one. The next kata (Sato) is essentially the same, except the attack is from the swordsman’s left. In the third kata (Uto), the attacker appears from the right, and in the fourth (Atarito), the attack comes from behind. Though the essential sword techniques are the same, the footwork involved changes. In Shohatto, the swordsman steps out on the right foot with the initial counterattack; in the second kata, she turns to the left and steps out with the left foot. For the third kata, it’s the right foot again, and for the fourth kata, the iaidoka pivots 180 degrees to the left, stepping out with the left foot again.

Each of these variations on Shohatto call not only for different footwork, but the timing of the initial draw and cut is different for each one of them. Learning these differences in timing is important. Learning to turn to the opponent – wherever he is – is also important. Starting from the kneeling position of seiza allows a student to explore these techniques in relative safety. Having to rise and move from that kneeling position gives you quads of steel.

For a long time, I felt that the physical conditioning and learning to variously time the counterattacks depending on one’s relative position were the most important aspects of learning to perform these kata properly. While these physical aspects are definitely important, they are not the only training that is going on here. Learning and practicing the variations of Shohatto (considered the most important kata of the set) also develops something else – fudoshin (不動心).

Fudoshin has been described as “immoveable mind.” While I think that sounds romantic, I am not sure that is the most accurate way to describe the term. “Immoveable” suggests being, literally, unmoved – perhaps, undeterred no matter what gets in your way, for example. But as one examines examples of fudoshin, one finds out that it means being able to adapt to whatever occurs. One writer has described this as being paradoxical – having an “immoveable mind” means that the mind does not get “stuck” mulling (or panicking) over an unexpected circumstance.

Fudoshin, however, is not paradoxical if you consider the term to mean “imperturbable mind” (another acceptable interpretation). Now things start to make sense. No matter what unforeseen circumstance gets in the way, the imperturbable mind will adapt without being thrown by whatever happens.

Once I started thinking about fudoshin in this way, the meaning of the variations on the first kata in the Omori ryu started to make more than physical sense. Not only were new students learning changes in timing and footwork, they were learning to adapt to the different circumstances being offered – an elementary introduction to fudoshin.

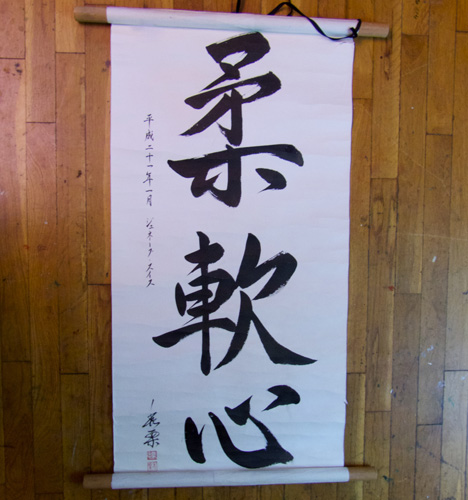

One of my budo colleagues, a noted student of calligraphy, once gave me a scroll, pictured above, which I still have, even though it is somewhat worn around the edges. It says – “ju nan shin” – flexible mind. I appreciated this scroll intellectually, but now I am beginning to understand it on a deeper level. No matter how many years I practice, I still learn new things with every new student who comes in the door.

[This post was inspired by the Budo Bum (aka Peter Boylan) blog post “States of Mind: Fudoshin,” March 19, 2015]