Charles Dunbar ◆ October 21, 2014

Mountains are powerful places. Not just in terms of majesty or picturesque beauty found in nature photography, but often the source of powerful folklore and local legends. Any culture that lives in or around mountains tells stories about them, and the fanciful denizens that live within them. Whether it be from the mystery of forests growing up the sides, or the sheer scope of them rising high into the air, people look at mountains in awe or reverence, and allow their minds to wander.

The folklore of Japan is no exception. From sacred mountain kami, to mystical ogres and even more fanciful creatures, the mountains of Japan have played host or setting to countless tales of wonder, and occasionally woe. These are places not just of rich creative power, but often symbolically real power, which draw people onto their slopes in search of the fantastic, or a deep inward journey. Seclusion on the sides of mountains has been greeted with respect and satire over the centuries, with a select few calling these places home full time. History and lore speak of men such as the yamabushi, who use the power of the mountains to further their ascetic pursuits and magical skills, and also of yokai like the tengu and the kijo, who prowl the slopes seeking out prey.

Much of this mountain lore has been historically established. The four “major mountains” of Japan- Fujizan, Hieizan, Kuramazan, and Osorezan- are practically kami in their own right. Hieizan and Kuramazan are the ancestral homes to Tendai and Shingon Buddhist schools, and the latter holds claim to the largest cemetery in Japan. Both are places of incredible spiritual and vital power, and are home to monasteries and men of learning, who elect to live on their slopes in the pursuit of enlightenment or perfection. Fujizan is often depicted in art and culture as a symbol of Japan as a nation, occasionally synonymous with the spiritual landscape and people it towers over. And Osorezan is a caldera of sulfur and volcanic ash, unfit for habitation, but viewed as the gateway between the lands of the living and the lands of the dead, where pilgrims visit departed loved ones before the journey into the afterlife begins.

But mountains aside from these great four are still scene both culturally and historically as places of power. The scholar Yanagita Kunio wrote of the power of mountains in his book Tono monogatari, where he spoke of them as retreats for people displaced by Japanese society who desired shelter from the onrush of civilization. Whether by force or by choice, these “yamabito” as he called them would eek out existences high above the plains, where the inherent magic of the mountain would transform them into something unique, and mighty. Occasionally these transformed men would come into contact with the descendants of those who displaced them, and conflict would ensue.

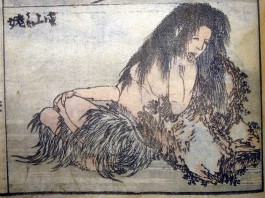

The kijo represent one of these legendary intersections between man and monster. Kijo, often dubbed “female oni” by writers and scholars, are often said to live in caves up high in the mountains. The most famous ones- Onibaba and the Yama-uba- are frightening femme fatales, known for ambushing or luring travelers into their caves, where they would be slow-roasted on a spit, while the hag looked on. Pregnant women were a favorite target for the Onibaba, as she sought redemption for failing to acquire the liver of an unborn baby for her mistress while she was alive. The Yama-uba was a mighty creature that strung her victims upside-down and bled them dry, initially for her own use, and later as the guardian of the hero Kintaro as she nursed and raised him. The Yama-uba’s transformation from hag to fiery mother figure might not have been attributed to the mountains, but they were her home regardless.

And then there were the tengu, avian horrors supposedly twisted by anger and mountain magic until they were large, humanoid crow-things, that swooped down from those sacred places to sow trouble and discord on the people below. Inhumanly strong, vicious fighters, and capable of flying great distances, stories of the tengu snatching up women, children, animals, and crops were commonplace in many of the areas Yanagita visited in the late 19th century. But stories of their presence were recorded as far back as the Heian period, when pilgrims and travelers recorded meeting with red-faced men living on the sides of mountains. He inferred that many were related to the people forced upwards as the Japanese ancestors emigrated to the islands, but that they were more than simple monsters, and capable of great learning. Tales of tengu transforming after meeting with Buddhist ascetics are found in the literature, and some of the greatest of the yamabushi, like the powerful Sojobo, are often said to possess tengu powers themselves.

And then there were the tengu, avian horrors supposedly twisted by anger and mountain magic until they were large, humanoid crow-things, that swooped down from those sacred places to sow trouble and discord on the people below. Inhumanly strong, vicious fighters, and capable of flying great distances, stories of the tengu snatching up women, children, animals, and crops were commonplace in many of the areas Yanagita visited in the late 19th century. But stories of their presence were recorded as far back as the Heian period, when pilgrims and travelers recorded meeting with red-faced men living on the sides of mountains. He inferred that many were related to the people forced upwards as the Japanese ancestors emigrated to the islands, but that they were more than simple monsters, and capable of great learning. Tales of tengu transforming after meeting with Buddhist ascetics are found in the literature, and some of the greatest of the yamabushi, like the powerful Sojobo, are often said to possess tengu powers themselves.

Whatever the case might be, legends like these speak to the power and respect ascribed to the mountains of Japan. But this reverence is almost universal in cultures the world over. The Japanese yokai just happen to have better PR.