July 27, 2014 ◆ Charles Dunbar

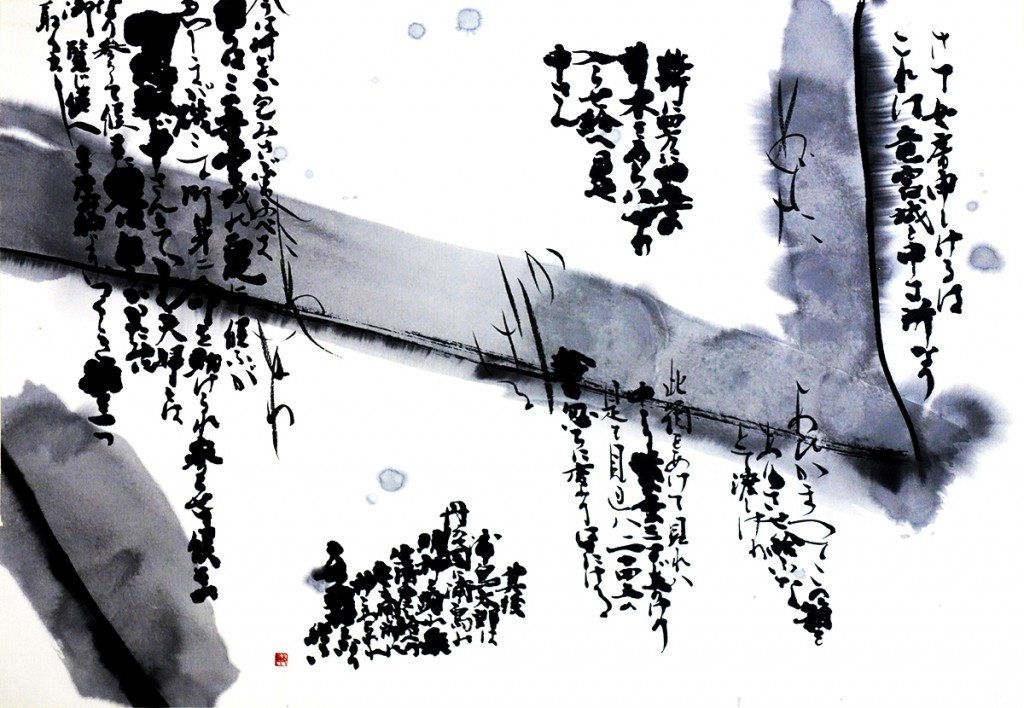

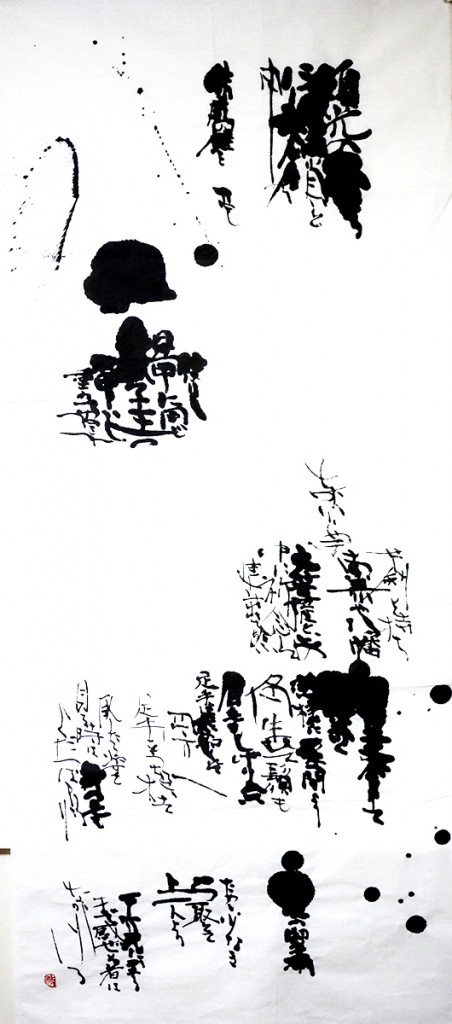

In Bokusai, Shoko Kazama’s new exhibition, she blends the contrasting colors of black and white Japanese calligraphy with several famous otogi-zoshi tales from Japanese history. But what exactly are otogi-zoshi tales?

The term itself is derived from an anthology written during the Muromachi period that told stories related to lessons found within Buddhism, fantasy, “worldly concerns,” and satire. Though often aimed at children, some of these tales have had connotations also linking them to politics, themes of loyalty and honor, bravery, and the glory of the Emperor. Above all, these tales were meant to be entertaining, with the added lessons lessons and moral questions blended into the narratives themselves, not unlike western fables or folk tales. Indeed, the “companion” stories, as they were often referred to, were one of the many different methods of storytelling found within Japan throughout the past thousand years.

Some of the most famous otogi-zoshi tales contained a number of familiar aspects: a noble hero, a task to be accomplished (usually related to honoring the self or one’s lord), and an oni. The hero ranged from the “everyman,” to the noble samurai, to even the outcast trying to prove his worth despite some external, perceive flaw. The task would center on a journey, or around the protection of an august personage, or even some dangerous task that few would possibly attempt, usually ending up with the hero facing down a monstrous “ogre” that posed a challenge to authority, or threatened violence to the person under the hero’s guard.

Two of the tales in the Bokusai exhibit- Shuten-Doji and Issun-Boshi- are examples of this type of otogi-zoshi: a hero facing down a monstrous entity, and proving their worth through dispatching of the malignant force.

Issun-Boshi, or “Little One Inch” as it is often translated in the West, is a children’s story. A lonely couple prays at the local shrine for a child, and are granted one…who is “no larger than a grown man’s fingertip.” Despite the obvious challenges placed upon one so small, Issun-boshi wants nothing more than to seek fortune and honor in the big city. Outfitting himself with a sewing needle “sword,” and dressed in the garb of a samurai, the boy travels in a teacup across a wide river until he reached the local town, paddling a lone chopstick as his oar.

Upon arriving at the town, little Issun-boshi immediately locates the manor house of the lord and offers his services. Despite his tiny stature, his insistence to serve (and subsequent oath of service, offered in the palm on the lord’s hand) charms the lord into making him a retainer to his noble daughter. Issun-boshi and the girl grow close, he as her “protector” and loyal attendant.

One day on a trip to the shrine, the girl is set upon by monstrous oni wielding a large hammer. Little Issun-boshi leaps into service, challenging the brutes with his needle-sword. The oni, large an fierce beasts, snaps the little “samurai” up and swallows him. But even in the pits of the monster’s stomach, little Issun-boshi pokes and stabs at the oni until it spits him up. Issun-boshi them stabs the monster in the eyes, and the creatures flee, but not before dropping their hammer. Using its magic, the princess manages to grow Issun-boshi to full size, and they live happily ever after.

While the moral of this story is fairly obvious, and entertainingly conveyed, Issun-boshi is not the only samurai forced to deal with the oni. In the tale of Shuten-Doji, the oni in question is far more fierce, and deadly- proving that these are not all tales for children.

Rather than ambushing the young princess on the way to the shrine, Shuten-doji and his band of brigands are a group a chaotic, vicious blood-drinkers, angry at the reign of Tenno Ichijou, and willing to slake unnatural urges on the women of the court. Kidnapping females, slaughtering samurai, and challenging Ichijou every step of the way leads to a pronouncement: the oni must die. The chaotic actions and vicious appetites are a threat to all Japan.

Into this fray is thrown Minamoto-no-Yorimitsu, known as the hero Raiko. Gathering together his four noble guardians, they disguise themselves as yamabushi (mountain priests) and bluff their way into Shuten-Doji’s fortress on Oe-yama mountain. After witnessing horrible dances, and a feast of blood and flesh, Raiko and his men wait for Shuten-Doji and his grim comrades to sleep before seeking him out, slaying him in his bed, and cutting off his head while he laughs in defiance and anger at receiving Ichijou’s judgement.

Unlike the oni in Issun-boshi, which were comical villains the tiny boy scared off, Shuten-Doji and his men were a true threat to the safety and sovereignty of the government. Avatars of chaos and rage- not unlike the oni of mythology that hunted the mountains and punished wickedness in the underworld- they sought vengeance upon Ichijou’s citizens and only through guile and valor could they be defeated, and balance restored.

Two hero tales, two different lessons, but the same outcome: the valorous triumph, and wickedness falls. Keep this in mind as you explore Bokusai, with its rich contrast and vivid calligraphy.